librdx

Escher’s art and computer science

While on a small vacation in the Hague I had a blissful chance

to visit the Escher’s museum. It is now hosted in an actual

royal palace which many Europeans may find surprisingly modest.

Maurits Cornelius Escher was a 1940x Dutch graphic artist known

for his math-rich works. As an author of a math-rich RDX data

format and the

While on a small vacation in the Hague I had a blissful chance

to visit the Escher’s museum. It is now hosted in an actual

royal palace which many Europeans may find surprisingly modest.

Maurits Cornelius Escher was a 1940x Dutch graphic artist known

for his math-rich works. As an author of a math-rich RDX data

format and the librdx library, I realized that Escher offers

powerful metaphors that explain many of my personal level-ups

earned during the lifetime of this project.

Replicated Data eXchange format is definitely an ambitious project. It is all at the same time:

- JSON like document format (JDR, “JSON done right”),

- binary serialization format (RDX per se),

- LSM key-value store,

- local-first data synchronization system,

- Merkle-graph (i.e. crypto-enabled) data store.

There are more aspects to it, but these are the key ones.

Being all of that, librdx stays quite minimalistic: 20KLoC

so far, including 6KLoC of generated parser code.

Escher’s metaphors capture the fluid spirit of this kind of work and thus explain to myself and maybe to others, why did I stick to it for so long.

So, here are the insights, if you care to listen.

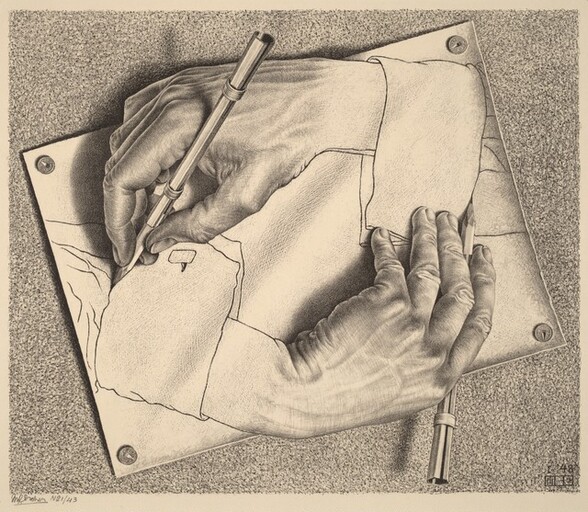

“Drawing hands”: develop tools using the tools you developed. That is self-evident when you do an orderly construction, like putting a brick on a brick. For example, I first developed a JDR parser, then I wrote a small JDR based test framework (very handy), then I was able to test RDX merge rules systematically, using all the norms of literate programming. I put the spec and tests side by side, so tests are explained and the spec is always tested in the most direct way. Then, I was able to build the LSM/SST store logic using all of the above.

That brick-on-a-brick approach requires some skill, and it is rational and incremental. The tricky part is some dependency loops often being hidden in plain sight. For example, the parser uses merge and ordering rules to normalize the inputs: if a map mentions the same key twice, these entries get merged. The bottom “brick” relies on the top “brick”!

This effect is best explained in “Reflections on Trusting Trust”. Long story short, you need a compiler to compile your compiler. And that has non-trivial consequences. The most breathtaking experience of this kind was using a parser generator to generate its own parser for its own eBNF rules. That code sort of spiraled itself into existence, feature by feature.

The most exciting part of it all is seeing how an idea becomes

a plan and a plan becomes working code (and the working code

amends the plan).

The most exciting part of it all is seeing how an idea becomes

a plan and a plan becomes working code (and the working code

amends the plan).

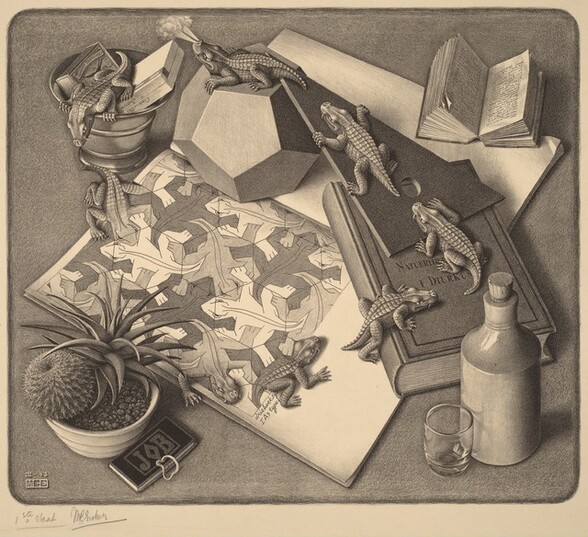

librdx had plenty of such rollercoaster stories and the topmost one

is RDX tuples. What is a tuple? That is several elements slapped

together. Should not be too complicated!

But, tuples have so many uses in RDX.

An ordinary tuple is something like 1:2, two numbers.

Tuples turn sets into maps, i.e. {1 2} is a set and {1:"one" 2:"two"} is a map.

An empty tuple is a something-but-nothing value, the most nullish null ever.

A tuple of one can be a “tombstone”, a placeholder for deleted data,

which is a necessary construct in distributed systems.

Tuples can express relational records and that is absolutely fundamental:

73456:"Alice in Wonderland":"Carol, Lewis".

A tuple is a construct that stitches so many things together.

In general, parts of the system interact. For N constructs, the number of

interactions can optimistically be estimated as O(N^2) (pairwise)

and pessimistically as O(2^N) (any group).

It takes time to fit the pieces of this puzzle together.

That is why I use C: C++ or Rust have much bigger N.

Frankly, everyone knows that C++ messed this part up.

C is so much simpler just because its N is small.

Still, I break the C compiler at times.

Like, a fancy macro and const-ness of value interacted in an uncommon way

with some compiler optimisation, bang!

But then, eventually, you get to the stage when everything works smoothly together. Half a year later, you don’t remember how it works just because it always works. All fits, it’s live!

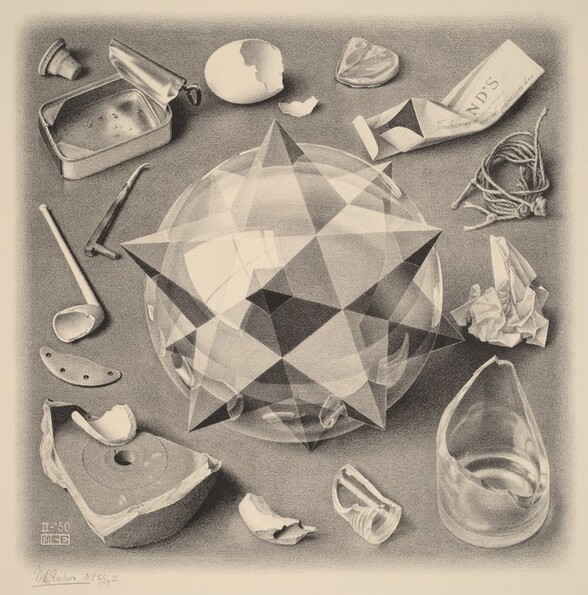

A good system orders itself.

That might as well be a fundamental property of living matter:

consume some random inputs, produce order and beauty.

A good codebase has rules and conventions in place

to structure incremental contributions.

You may not be doing the best you can every particular day of a year.

But, as you add more code, the codebase does not turn into spaghetti.

Maybe not today, but eventually every piece will fall into its right place

just by some Brownian motion.

That kind of crystallisation is a powerful ability.

There are rules and policies that define the right place for each piece.

Not too many rules, so you can remember, but just enough.

A good system orders itself.

That might as well be a fundamental property of living matter:

consume some random inputs, produce order and beauty.

A good codebase has rules and conventions in place

to structure incremental contributions.

You may not be doing the best you can every particular day of a year.

But, as you add more code, the codebase does not turn into spaghetti.

Maybe not today, but eventually every piece will fall into its right place

just by some Brownian motion.

That kind of crystallisation is a powerful ability.

There are rules and policies that define the right place for each piece.

Not too many rules, so you can remember, but just enough.

There have been some rules that worked like a “comb for the code”. For example: “a buffer (4 pointers) owns the memory; a slice (two pointers) does not”. This one helped to fix an impeding chaos in function signatures and memory management.

librdx employs a rather special (I say “algebraic”) function naming convention.

Names like $$u8cfeed1() may look scary at first but once you get the system, the order emerges:

“feed a byte slice into a slice of byte slices”.

Then, HEAP$u8cpushf() reads naturally as

“push a byte slice into a heap of slices, as ordered by the function”.

Method naming is sort of a pain point in C (cause yes, C has no methods).

So, that convention replaces the C++ type system and name mangling.

Once the convention was in place, not only the naming,

but also the general code organisation improved.

Good rules build the system.

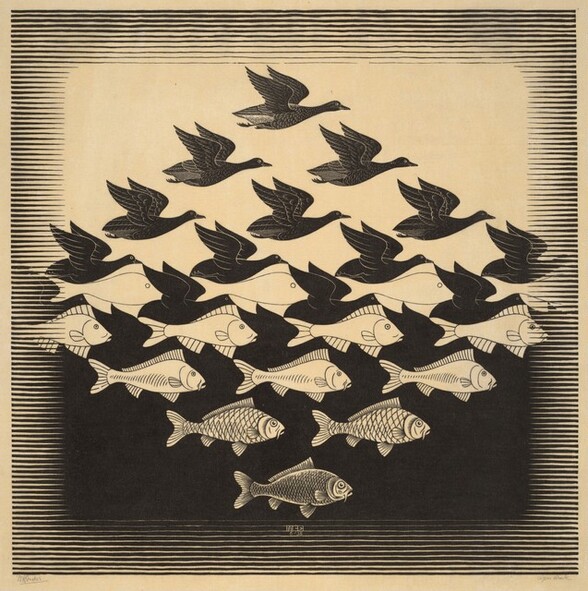

*Separate the defining features from meaningful from unimportant.

Or, “divide, define, derive”.

It is a good practice to focus on the key parameter that affects

everything else, and let the other tunables be derived from that.

In other words, focus on the bottleneck,

separate fundamentally different things as early as possible.

*Separate the defining features from meaningful from unimportant.

Or, “divide, define, derive”.

It is a good practice to focus on the key parameter that affects

everything else, and let the other tunables be derived from that.

In other words, focus on the bottleneck,

separate fundamentally different things as early as possible.

One relevant story is probably the skip list template, SKIPu8feed() and friends.

librdx uses C templates extensively, which C in theory does not even have.

In fact, the Linux kernel uses C templates a lot.

librdx templates are normally parametrized by a type, e.g. X(B, push1) produces Bu32push1().

In the case of SKIPu8, a skiplog (an append-only skiplist) has a critical parameter: size of a block.

Everything else is sort of dependant.

The block size is conveyed through the bit size of a block offset variable, e.g. u8.

Once you say you use one byte for the offset, everything else tunes itself.

At a first glance, that seemingly limits us to 256 or 65536 byte blocks.

On the other hand, if we absolutely want 4096 byte blocks,

nothing prevents us from defining typedef u16 u12 to instantiate SKIPu12feed().

Earlier versions used more parameters for the template, very much like a typical C++ codebase does.

That eventually turned unnecessary.

Once you specify the key parameter everything else depends on,

other choices can follow naturally.

Less is more!

These are genesis moments of those little software worlds. At creation you separate water from land, so those who live in the air will grow wings and those who live in the water grow fins, for the most part. Although it may take more than seven days of building to get to any meaningful result, but it least you felt almost like a god for a moment.

What I described here is very much the opposite of vibe coding. It is more about the value of some subtle and hard to verbalize experiences that separate juniors from seniors, seniors from experts and experts from gurus. Once a decision is made, you have to work hard for a period of time just to know the outcomes. This is why the experience is important: a senior developer can resolve a situation that an expert developer would never get into and for a guru it will never occur.

The best way to convey that experience is probably a koan. Or Escher.